A Conversation

with Alan Alda, Peter Parnell and Gordon Davidson

Moderated by Frank Dwyer

Reproduced from Performing Arts Magazine, March 2001

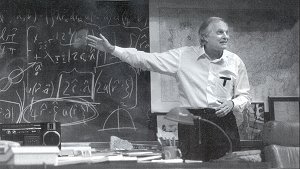

Alan Alda as Richard Feynman

DWYER: “QED,” Peter Parnell’s new play about the physicist Richard Feynman, is just beginning its previews as we talk. I know QED means Quantum Electrodynamics, which was Richard Feynman’s field, and also QED is the abbreviation for ‘quod erat demonstrandum,’ which basically means ‘that proves it.’ But how did we get here?

ALDA: I brought a book to Gordon about six years ago called Tuva or Bust! written by Ralph Leighton. It’s about the last few years of Feynman’s life, and I said to Gordon that it might make a good play. What interested me about it was that it captured an aspect of Feynman’s personality that I thought was fascinating – his ability to see something worth doing in apparently the most trivial pursuit. Getting to Tuva, this country that nobody ever heard of, that he only knew from his boyhood stamp collection. He only thought Tuva was interesting because there were no vowels in the name of its capital city, Kyzyl. But everything he did led to something else. That was the way his brain worked.

DWYER: He had a kind of essential playfulness.

ALDA: Yeah, an essential playfulness that was very serious to its core. And to me, this wasn’t just an image of Feynman’s character. It represented all humanity trying to understand, and being kind of heroic in the process – to understand the world and whatever part of the universe we can see. It’s heroic because Feynman never lets him self believe something he can’t test. And he doesn’t try to convince anybody else.

DAVIDSON: What fascinated me was that the book was more about a journey than a destination. Feynman and Leighton were trying to get to Tuva, of course, but what the book was really about – and what Feynman’s life seems to have been about – was how you travel somewhere in the life (of the mind or the spirit or whatever. The book also struck chords in me because I knew Feynman a little bit, when he was at Cornell and here at the Taper. When I did The Genius, Howard Brenton’s play about a physicist, I invited Feynman to see it. In the play, Brenton’s physicist comes up with the next important theory but is afraid it’s going to be misused by government agencies. Finally, though, he comes to understand something crucial: you can’t hide knowledge, you can’t turn it off, you can’t disguise it. Nature. ‘You can’t fool nature’: that’s what Feynman would later write at the end of his report on the Challenger disaster. Feynman sat there just shaking his head at Brenton’s play, because of that essential truth – that ideas have a purity to them, though they can be appropriated and put to some other purpose. I thought about that again, as we worked on this play and discovered Feynman’s reaction to the atomic bomb… When I read the Tuva book, I said, ‘I think it can be a play, Alan, but I don’t know what kind of play.’

ALDA: I didn’t either.

DAVIDSON: And then I gave Peter the book, because he had done such an amazing job on The Cider House Rules.

PARNELL: I read it, and I thought this is going to be easy. [General laughter.] I responded to the things Alan and Gordon have talked about: the fun of the journey itself. I felt it could be done simply. I wasn’t sure the Tuva story would be the only one in the play. I got intrigued by Feynman, and I read Ralph Leighton’s other books. I was most moved by a scene in the Tuva book. Feynman and Leighton have tried every which way to get to Tuva, Feynman is quite ill, and they take a walk through their neighborhood, pretending they’re in Tuva. Then I read accounts of the last years of Feynman’s life, and I found that the story, the background of the Tuva book, was very powerful. I began thinking I was just going to dramatize the Tuva book, but more parts of his life started flooding in, and the idea started to change.

DAVIDSON: I remember that scene, when you tried to dramatize the walk. Leighton said to Feynman, ‘Let’s walk this way,’ as if they were in Kyzyl…

PARNELL: The first time I met Michelle, Feynman’s daughter, we had dinner and then we drove to their old house, and through that Altadena neighborhood.

ALDA: It’s very interesting meeting people like Ralph who knew Feynman so well for so many years. And then at Caltech, meeting the people who knew him really well and loved him. His secretary, Helen Tuck. It was like going to a cabinet where cinnamon has been stored but it’s no longer there. You can still smell the cinnamon but you can’t quite get yours hands on the spice itself. We have this impression of Feynman from so many different points of view. It’s a little bit like Feynman’s own theory of every single photon taking every possible path at once. We’ve had this joke among us. What we ought to do is a play called ‘Three Guys Sitting in a Hotel Room Talking About Feynman’ because, for years now, we’ve been trying to find out who Feynman is. I think finally, without knowing exactly how, a Feynman has emerged that will probably be convincing to many people. But it’s very hard to get to know him.

DWYER: You seem to be describing one of Feynman’s own guiding principles. He said that the thing that doesn’t fit is the thing that is most interesting.

ALDA: The thing that surprises you. You’re going along, everything seems to be okay, and the thing that surprises you turns out to be the most interesting thing of all.

DAVIDSON: One of the constant themes is what’s interesting to him. How it awakens him. The way a student asks a question or…

DWYER: The way a plate spins in the air…

DAVIDSON: And he always wanted to work it out for himself.

PARNELL: He’s a very tough guy to dramatize because he contained the contradiction. He was the kind of thinker who could see both sides – or many sides – of a problem. He could solve a problem by actually looking at all the different parts simultaneously, which means in a funny way he was able to play pro and con, black and white, be all the parts himself.

ALDA: To a great extent that’s how the play works. He’s so many different people. There’s a book about him called No Ordinary Genius – that’s how somebody described him. His brain was so special that it could visualize the interactions of subatomic particles. There must be very few people who have ever lived who can do that, and who can also play the drums, and draw really, really well, and tell a story so that it’s hilarious, captures your interest, gets you to see things at another level. He could be funny during a lecture. There are people who get paid a lot of money and that’s all they do is make jokes. This guy could do that and physics. And the way he thought was, to me, the most heroic part about him. When I think about what people could take away after two hours of being with Feynman, I think wouldn’t it be nice if they got a little flash, a little glimmer, of what it’s like to think the way he did: to always challenge your own assumptions, to examine everything with curiosity, as if you’d never seen it before, to take every solution that already exists and re-examine it, re-solve it…

DWYER: What particular challenges did the material present for three non-physicists?

ALDA: The only slight challenge we had was not knowing what we were talking about. [Lots of laughter.] If that’s important to you, I suppose that’s a challenge.

DAVIDSON: Right. And that’s the kind of thing that takes a lot of acting.

DWYER: The process seems to have gone very well for the three of you. How do you think it would have been if you’d had a fourth collaborator, if Feynman had been around?

DAVIDSON: He is around. He won’t leave us alone.

ALDA: I think it would have been just as hard. Everybody who knew Feynman has a memory of him that’s very pungent, and each one is very different.

DWYER: He’s the thing that doesn’t fit.

ALDA: Yes, that’s what makes him so interesting.

DWYER: I want to go back to Peter’s point. You said that the way he seemed to encompass contradictions made him hard to dramatize.

DAVIDSON: We started with the Tuva book, but it soon became apparent that, though it was rich and evocative, it wasn’t a play. Peter was the first to see that. So we kept trying to figure it out. We’d sit in a room like this, we’d sit in Alan’s house, or in the rehearsal rooms here, and simply try to figure out how to tell this complex story.

ALDA: And, Peter is … I never worked with anybody so indefatigable. He wrote many different plays. Not drafts. Entirely different plays.

PARNELL: I was amazed myself.

DAVIDSON: Has that happened before?

PARNELL: No. I don’t know what happened on this. I was obsessed with the idea. I remember reading once how Feynman, when he was trying to solve a problem, would not let go. But he was smart enough to pick the right problem, which is a very important thing. He knew how to leave the problem or turn it on its ear in such a way that if he needed relief from it, he could get it. And I used to think I can’t get away from this and yet I don’t want to get away from it. It was a very dogged, determined, at times hellish, always very challenging, stimulating thing. Both Gordon and Alan were amazing because they went every step with me helping me with each approach. They didn’t give up either.

DAVIDSON: And other actors were helpful too.

ALDA: Most of the plays Peter wrote for us had large casts.

DWYER: Ralph Leighton was a character at one point?

DAVIDSON: The mother, the father.

ALDA: Hans Bethe, Einstein, all kinds of people.

DAVIDSON: I have a feeling that Peter had to go through that process to get to what we have.

DWYER: To find his essence, by bouncing him off other people?

DAVIDSON: And the essence is not a docudrama. It is very much of the theatre, and very much of the aura and the essence of Feynman himself. There are interesting surprises in the play, but it is really climbing inside a man’s mind and his spirit.

DWYER: One of the things I learned from the play was how fascinated Feynman was with the theatre. When he saw your production of The Genius, Gordon, did he only comment about the physics, or was he also interested in the stagecraft?

DAVIDSON: Yeah, he didn’t like it.

DWYER: If he were here now, he’d probably want to be in “QED.” He’d want to play a small part and steal the scene.

ALDA: Why a small part? He’d want to play Feynman. I’d be the guy on the phone. [Laughter]

DWYER: John Keats said that every man’s life was a continual allegory, and looked at closely…

ALDA: Now that’s another thing Keats said that I don’t understand. Didn’t this guy ever speak English? What’s that other thing about…

DWYER: Negative capability?

ALDA: Yeah, negative capability. Tell him to take a rest. [Laughter]

DAVIDSON: You think that’s Alan speaking. It’s Feynman.

DWYER: I’ll rephrase my question: what can people learn from looking closely at Feynman’s life? Alan has spoken about the possibility of learning to think a little like him, and re-examining everything we think we know. What else should people take away from “QED”?

DAVIDSON: I don’t know if I’d want to prescribe that. The play has many different entry points. We spend two hours. with a man you can’t help but be interested in – the way he sees his life, conducts his business, examines who he is, and relates science to everything else. But the overriding thing is his connection to nature, and how important it is to under- stand what that means. Remember, Feynman was a teacher… he wasn’t just a lecturer, a gagman, a musician…

ALDA: There’s also a very good story here, a strong theatrical experience. If you go through that experience, something will happen to you that happens to people in good theatre. It’s much more than what I said before about experiencing his thinking. It has to do with transformation, with a release to a higher way of seeing and experiencing. To the extent that the audience can go through that, that’s what they come to the theatre for.

DWYER: Do you anticipate any difficulties from what Feynman described as the prejudice so many people have against science.

ALDA: The folks at Caltech who knew and loved him said he had this incredible ability, no matter who was in the audience, to explain physics so simply that people actually believed they understood what he was saying. They compared this to the old joke about Chinese food, because an hour later you were dumb again. [Laughter] But at least while you were listening, it sounded pretty good.

DWYER: I know that in the Tuva book, Feynman and Leighton are playing the game Geography, and Feynman thinks he can stump Leighton with Tuva, a country he only knows about because he has a Tuva stamp in his old stamp collection. Didn’t that story have a special resonance for you, Gordon.

DAVIDSON: Well, when I read that and we started talking about it, I said, ‘Tuva, I think I remember that.’ I tried to find my own stamp book, which I had passed down to my son, who gave it to his cousin, who passed it along to another cousin. It came back when everyone lost interest in stamps. When I was growing up, stamps were a great adventure. I guess kids watch television now, travelogues, you know… but that was the way you traveled in those days. It was great, really great. Anyway, I tracked down my stamp book, which is dated 1947, opened it to the page, and there was one of those beautiful triangular stamps… That’s just a coincidence, the way there are coincidences in one’s life – how you connect certain dots…

DWYER: You all seem to have had a good time on your own Tuvan adventure.

DAVIDSON: I don’t think we’ve ever gotten tired or bored, because there is so much to peel back. If this were only a history or biography lesson, it wouldn’t be as interesting as trying to make a play, trying to make it live in the theatre. The magic of theatre is how you can take disparate things and get them to resonate, get them to keep knocking against each other, like photons and atoms, and causing reactions. I was thinking just this morning about the whole question of photons and electrons and the charge field and what have you.

ALDA: Were you talking about that with Judi at breakfast? [Laughter]

DAVIDSON: No, before breakfast, while I was still in a stupor. About how the play does a lot of what Feynman describes. About the fields of force in his life, and how one thing resonates off another. Not that he necessarily was thinking this particular thought while this was happening. The playwright has to put the thoughts and actions in context.

PARNELL: Well, we’re in the presence of an extraordinary mind, a man who can think unconventionally and in unique ways, and who is undergoing something that is universal.

DAVIDSON: There’s something in the essence of this man that allows us to go on the journey with him, to find out what the real journey is. Not the Tuva journey but the real journey.

ALDA: The wonderful opportunity for us is that he was a genius who made a very great point of speaking simply about the most complex things. He said, in fact, that if you can’t say it in simple words, you don’t understand it. He didn’t like fancy parties or clubs. He didn’t like prizes. He deliberately maintained his regional, New York accent. He very deliberately remained a regular guy. And when people are in his presence, even though he is vastly smarter than almost everyone – not just in the room but on the planet – they are not in the presence of someone who gives the impression that you need to stay where you are. If you listen and try to catch on, you can make a little progress along with him. And he’s with you in the process; he’s not apart from you. He wrestles with the very same things that we all have to cope with before we finish here on earth. And that makes him extremely appealing. It’s not like you’re going to see the intellectual history of somebody that you can’t understand and don’t want to spend very much time with. This guy just throbs with vitality and humanity.

DAVIDSON: He communicates this extraordinary sense of well-being. You feel you’re with a friend who is somehow going to make you think better. And the other thing I’m learning is … you know, I guess chemists do experiments and they watch … but he did it all in his head and his imagination…

ALDA: He did real experiments, too. And he would do them at the drop of a hat. Once, he and a friend were making spaghetti. And the friend said ‘why is it when you break dry spaghetti out of the box, it always breaks in half?’ So they spent the night breaking dry spaghetti together trying to figure out – did it always break in half? Why did it always break in half, if it did? There was nothing that didn’t interest him. Who cares about how spaghetti breaks but, in fact, if you know how spaghetti breaks, you might find out how steel beams in a bridge break. You never know what you’ll find.

PARNELL: And how the world works. And where that leads you. That’s another big thing for him. If you look at anything closely enough, it’s going to get interesting, or lead you some place interesting.

DWYER: I have a final question. Which of you now knows more about physics? PARNELL: I’d say Alan.

DAVIDSON: Definitely Alan.

DWYER: Alan, were you always interested in science?

ALDA: When I was about six years old I used to do experiments in my bedroom. To me that meant mixing household ingredients like toothpaste and baking soda, anything that would mix, to see what would happen. Thank God nothing happened. Now I know that there are certain ingredients that, had I mixed them, would have caused a small explosion. Fortunately, I couldn’t reach them.

DWYER: You can reach them now, so we’ll be expecting a small explosion, and a strong whiff of cinnamon. Q.E.D.